This post was prepared for a roundtable on Comparative Constitutional Design, convened as part of LevinsonFest 2022—a year-long series gathering scholars from diverse disciplines and viewpoints to reflect on Sandy Levinson’s influential work in constitutional law.

Zachary Elkins

Sandy

Levinson’s oeuvre is so extensive that it surprised me to learn that his 1989

article on the second amendment was his third-most cited

publication.

The irony, of course, is the premise of the article: that scholars had largely

neglected the second amendment. Given that inattention, “The Embarrassing

Second Amendment” (“Embarrassing” hereafter) should be a “deep cut” from the

Levinson portfolio, not one of his greatest hits.

The appreciation of “Embarrassing” has increased in recent years, much like the Beach Boys’ album “Pet Sounds,” which flopped when it was released only to go certified platinum thirty years later. By no means did “Embarrassing” flop, but it has had late-life resurgence, with each year more popular than the last. Much like Sandy’s career.

That the article has increased in its relevance is indicative of the direction of the Supreme Court and gun culture in recent years. Consider another irony: the article’s relevance is despite Sandy’s zealous efforts to focus our attention beyond rights (and their interpretation) and toward the hardwired, structural elements of constitutions. Alas, Sandy’s Our Undemocratic Constitution may be woefully incomplete—at least one of the founder’s rights may have suboptimally and catastrophically constrained the translation of citizen preferences to law. Admittedly, it could be that structural improvements would be enough to bring our approach to guns in line with Americans’ preferences.

The

year 1989 evokes enough nostalgia that it is worth revisiting. The Soviet Union

had just collapsed, the Oakland A’s beat the Giants in an

earthquake-interrupted World Series, and “When Harry Met Sally” was on the big

screen (along with an impressive number of other memorable movies, at

least for me). And, of course, the Yale

Law Journal published “Embarrassing,” apparently 262 feet from where I

slept,

somehow blissfully unaware of any of these ideas. What was the “gun

environment” of 1989 in which Sandy pondered the second amendment, and how does

it compare to that of today? Evidently, gun deaths were just as prevalent as they are now, at least with

respect to suicides and murders. By contrast, interpersonal physical conflict,

such as fights in schools, has generally been on the decline since the 1980s

(with physical bullying replaced by a perhaps more vicious digital variant—which may be worse). Note, however, that the

pandemic seems to have led to a regression of sorts in school fights—welcome

to a world of physical and digital

conflict! And, of course, the rate of mass shootings has only increased, a grim

reality that has all citizens wringing their hands, without any agreement on

how to proceed. Actually, the violence feeds the fuel of partisan polarization,

which reaches a new low each year. Apparently, the steady progress in civility

that Steven Pinker, and other “progress” scholars, have noted over the centuries

is a longer-term process. In terms of violence, gun or otherwise, U.S. society

doesn’t look much different now than it did in 1989.

Likewise, it will not surprise anyone to learn that the text of the U.S. Constitution hasn’t changed since 1989 (save for the rightly famous 27th Amendment, enacted in 1992). And even that revision was scripted 230 years ago. What is significantly different is the interpretation and application of the second amendment. After centuries of not overturning much of any state or local gun regulation, the Supreme Court issued rulings in 2008 and 2010 that invalidated gun statutes and crystallized an individual right to bear arms. In 1989, Sandy could confidently write the following:

It is almost impossible to imagine that the judiciary would strike down a determination by Congress that the possession of assault weapons should be denied to private citizens. (p. 655)

Impossible to imagine in 2022 though? Sure, Justice Scalia’s opinion in District of Columbia versus Heller makes it clear that legislators can constitutionally constrain guns under many conditions, but that may be a very 2008, view. We are stepping into a decidedly different stream in 2022. Regardless, we may never have an opportunity to test Sandy’s specific assault weapon speculation given the improbablity of such a federal ban. The court did recently have an opportunity, however, to demonstrate whether there is any daylight between its thinking and Scalia’s Heller opinion. Specifically, the question during this Supreme Court term on a New York rule requiring “proper cause” for carrying a concealed weapon. As I wrote one month ago, “I’m not sure what the odds in Vegas are on the NY case (is there anything on which we cannot bet these days?), but I would put my money on invalidation.” The case is now closed: what is the German word for the regret-of-not-having-bet?

Suffice

it to say that Sandy was prescient. In 2022, we recognize all too well that we must take the second amendment

seriously, for better or worse. Think about this in the context of Ukraine and

Uvalde – events that shine a light on guns.

If any event demonstrates the relevance of “Embarrassing,” it’s the Ukrainian conflict. Remember, Sandy suggests that we take the idea of collective defense against tyranny seriously.

The unfolding Ukrainian war, on its face, makes a compelling case for collective defense. In a world of grey, the conflict couldn’t be more black and white—the kind of old-school, imperialist belligerence that the United Nations was devised to thwart. And almost nothing else seems to have brought most the world (and the US public) together more so than defending Ukraine. I notice just as many Ukrainian flags on Austin streets as I do U.S. ones. Participating in the conflict seems to involve the kind of “honor” that we haven’t seen for some 60 years. The war attracted volunteer combatants from outside Ukrainian borders, including two U.S. veterans now prisoners of war in Russia.

And guns are having a moment. Any male Ukrainian between 18 and 60 has been pressed into service and issued a firearm, if not a molotov cocktail. Few have seriously argued that ordinary Ukrainians should not take up arms in this way, or that guns should not be distributed so indiscriminately. If anything, the critique seems to be that Ukrainians do not have enough arms and ammunition. Indeed, one could argue that such a citizen mobilization has been effective strategically and, perhaps more importantly, motivationally.

By the way, it seems to me that we need to think more about the intimidation effect, for both good and bad, of arming citizens. It seems that governments may well think twice about oppressing armed citizens. But with that sort of deterrent, so goes deliberative democracy, which is the part of our democracy so in trouble these days. Brownshirts dominated the political discussion and intimidated opponents 60 years ago. It is hard to feel safe in a traffic dispute—much less a political debate – when your interlocutor is packing heat.

Still, the Ukrainian example is powerful: why shouldn’t a similarly disposed country have something like the second amendment? And why shouldn’t this justify the collective defense argument embedded in the prefatory clause of the second amendment?

Sandy’s article suggested that it wasn’t crazy to imagine such scenarios. He pointed to Tiananmen Square, Israel, and South Africa—places where the oppressed could use more muscle to deter real threats or where collective defense against outsiders was real. Of course, many of us have had a hard time imagining U.S. citizens facing off against either domestic tyranny or a foreign force. And indeed, very few scenarios have presented themselves, especially in the modern era. This cartoon by Tom Toles says it all. This is not to say that there have not been moments of state oppression for which armed resistance would have been helpful: think black Americans in the Jim Crow south.

And as

for foreign threats, most of our recent history suggests that Americans are

more likely to be on the invading side than on the invaded. The U.S. military,

after all, accounts for 2/3 of the federal government’s discretionary government

spending. Two-thirds! Congress appropriated a full $40 Billion for the

Ukrainian conflict, which is close to Russia’s entire military budget of $60

Billion. And not a single U.S. soldier is fighting in Ukraine, supposedly. If

the U.S. military budget does not buy collective defense, then the General

Accounting Office needs to get on the stick.

At the same time that we need to take the benefits of the second amendment seriously, we need to once again look at the other side of the ledger, which is grim. While we grieve the 24 children senselessly killed in their 2nd grade classroom in Uvalde, we wait for the seemingly inevitable next shoe to drop, somewhere else in the country. And it’s not just inexplicable mass shootings. As I cite above, homicides by gun, gun accidents, and suicides are as high as ever, just as other risks to human life have plummeted. Death by gunshot is now the leading cause of death for Americans under 25.

The

risks are high, and it’s not clear that the individual rewards of gun ownership

are worth it. Guns are very useful tools in some rural settings and most of us

recognize the need to defend oneself, especially those who feel vulnerable. Still,

99 out of 100 gun deaths are homicides, accidents, or suicides, for every 1

death that can be justified in terms of self-defense. Those are terrible odds,

especially when we consider that many of the accidents involve a shooter’s

loved ones. Of course, these numbers involve only those incidents in which a

gun has been fired. We do need to recognize that, in some situations, guns have

deterred assaults and robberies. But whether guns escalate or de-escalate

ordinary disagreements is a real question. It could well be that people avoid

confrontation with strangers (say, raging motorists) for fear that they’re

armed. It is also quite evident that conflicts that would have involved just

words or fists now involve guns, and fatalities. You don’t need a class in game

theory to know that one person brandishing a weapon increases the probability

that another will do so, and once two guns are brandished, well…I’ve never

understood the logic behind the movie scene in which two individuals draw their

weapons upon one another without either firing.

There

we have it. It is hard to predict when, exactly, we may need our citizens to be

armed. And mindlessly arming them doesn’t seem to work well. It seems clear

that the solution to all of this rests in the “well regulated” part of the

second amendment’s preface. No need to even think about the prohibition of

guns. Rather, collective and individual defense is best served by a highly regulated

program of gun management. Especially one that encourages creativity in the

kinds of regulation and technological safeguards—exactly the kind of thing that

has led to the decrease in auto accident deaths. Sensible right? But we’re no

longer in the realm of sensible political discussion. To decrease the

temperature, it has always seemed to

me that

one needs to both (1) preserve the right to arms and (2) enshrine the norm of regulation. That’s how most Americans

feel, according to survey research.

Rather than wrangle about what the founders could have meant or said, regarding the second amendment, why not look forward? Part of looking forward is to understand what we would do, however fantastic the notion. On what foundations would we build a new constitution? Having had the distinct pleasure of co-teaching with Sandy, I will tell you that he regularly engages in fantasy in this respect.

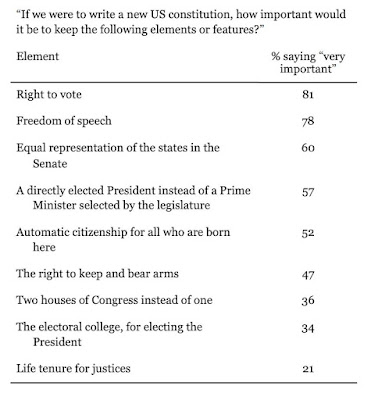

One starting question is how invested citizens would be in the various elements—dysfunctional and otherwise—of the U.S. constitution. Typically, I ask my students what they would add to the U.S. Constitution, but why not ask about subtraction? Or rather, on what current foundations would the U.S. public wish to build? Jill Lepore and I put the question to a representative sample of 2,000 Americans in a June 2022 survey on which we collaborated with the group, More in Common, whose mission is to understand and mitigate polarization in the United States and Europe. More specifically, we asked, “If we were to write a new US constitution, how important would it be to keep the following elements or features?” The results:

The U.S. public is not wedded to two houses of Congress, the electoral college, or much less so, life tenure for justices (and this before the rescinding of Roe v. Wade). On the other hand, they would retain freedom of speech, presidentialism, and the malapportioned Senate (presumably more so in Delaware and Wyoming, though I will check).

Evidently, as per our purposes here, almost half of the public sees the second amendment as foundational, though nothing like freedom of speech or even the right to vote (which is not even constitutionalized). For better or worse, much of the U.S. public is socialized to understand the right to bear arms as a foundational right upon which to build our society.

Zachary

Elkins is an Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin and

Co-Director of the Comparative Constitutions Project and Constitute. You can

contact him at zelkins@austin.utexas.edu.